Michael Essinger spends his weekends grading at least three sets of papers from three different classes at different colleges. At the same time, he is in the middle of the research for his dissertation for a doctorate degree.

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, Essinger teaches a history class from 7a.m. to 7:50a.m. at Fresno City College. Then he rushes to catch the train to U.C. Merced where he is a graduate student. He also spends one night a week teaching in Hanford or Visalia.

Essinger has been an adjunct instructor at FCC for the past five years. In these five years, he has had great difficulty making ends meet on the income he makes as an adjunct instructor.

An adjunct professor is a part-time professor who is hired on a contractual basis rather than in a tenure track or a permanent position, according to a definition on wisegeek.org. Colleges hire large numbers of adjunct faculty members because they are flexible and cheaper to maintain than traditional full-time faculty.

But just like regular faculty members, adjunct professors must fulfill basic educational requirements before they can teach, but they are do not enjoy the same compensations or other benefits such as health insurance coverage.

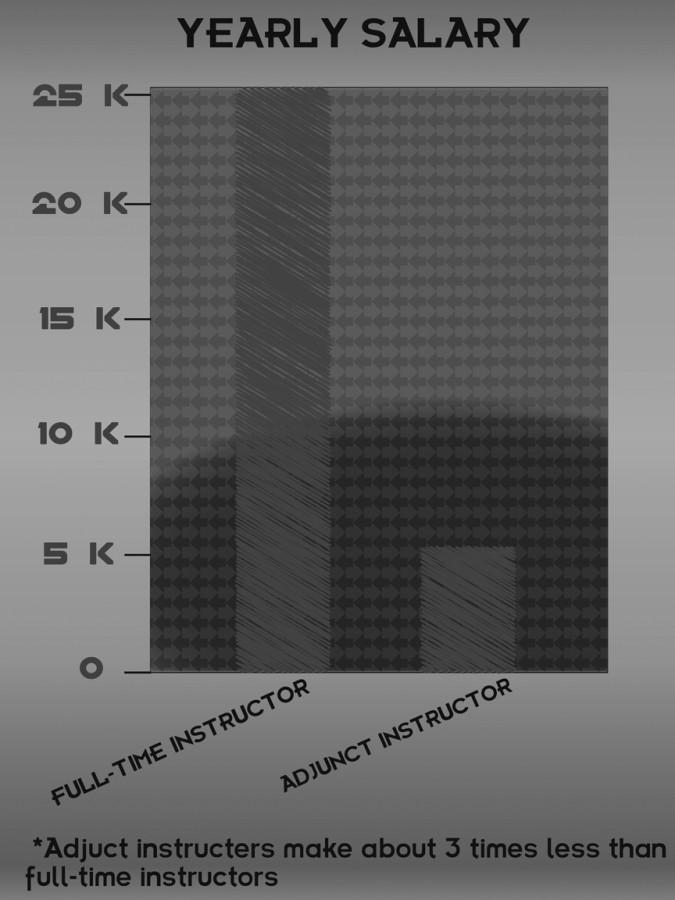

According to Essinger, the difference between what the adjuncts are paid to teach five classes — which is a full load for a tenure track instructor — and what full time instructors are paid is about $25,000 a year.

“We can’t make a living as adjuncts. We are limited to the equivalent of 3.5 classes at a community college in [the State Center Community College district]. I can only teach the equivalent of 3.5 classes combined between [FCC], Reedley, Willow, Oakhurst and Madera,” Essinger said.

To get an adequate load for his livelihood, Essinger must also teach at other colleges, some of them more than 50 miles away. Adjuncts at FCC also teach at College of the Sequoias campuses in Visalia and Hanford; the West Hills District in Lemoore and Coalinga and the Merced district with campuses in Los Banos and Merced.

“Adjunct faculty is a bargain for the administration. They get highly qualified, highly trained faculty. We all have at least master’s degrees,” said Essinger. “Many of us have Ph.Ds or are close to getting our Ph.Ds. We work for half of what it would cost if we were full-time teachers.”

According to the SCCCD institutional research, there are currently 954 adjunct instructors in the district. Forty percent of classes in the district are taught by adjunct instructors and the average salary for adjuncts is $47.49 per hour. In other words, an adjunct teaching a three-unit class grosses $142.47 a week or $569.88 a month.

“They [full-time faculty] have other duties, but the cost to the district is so much less for adjuncts, they go that way,” said Essinger. “For each class I teach here, I make about $380 a month. If this was my only job, there is no way I would make a living.”

Another concern that adjuncts feel is a lack of job security. According to the contract between SCCCD and the State Center Federation of Teachers Bargaining Unit, “part-time faculty are ‘temporary employees.’ Nothing contained in this section nor any article of this agreement places a legal obligation on the District to provide continuing employment for part-time faculty.”

Essinger says he lives with uncertainty from semester to semester and is never sure whether or not he will return. He feels this is a disadvantage for the students.

“Students may or may not have the opportunity to take me for other classes. I may not be back next semester. If a student wants me to write a letter of recommendation, good luck in finding me. I don’t have an office. I don’t have a phone number,” said Essinger. “If I’m not teaching, I don’t even have a mailbox. So there is this lack of continuity by using part time faculty; lack of support for students.”

Lacy Barnes, president of the State Center Federation of Teachers, Local 1533, has been working to bring about some change for adjunct instructors, “to increase the wages of our part-time faculty so that it is more of what is known as a pro-rata, a rate that is equivalent to or at least comparable to what a full-timer might get for doing the same work.”

“If there is no interest in the district desiring pay equity, we’re just talking to ourselves,” said Barnes. “We don’t have anything close to a pro-rata. Every time we go to negotiate, we try. ”

She adds that part-time instructors are paid hourly rates because the hourly wage is cheaper than paying a full-time salary.

Another goal of the SCFT is to make sure adjuncts get health benefits.

“We have argued to offer at least a buy-in, but the district has not had any interest in offering those benefits,” said Barnes.

Unlike full-time faculty, adjuncts are not required to have officers or serve on committees. But that can cause part-time instructors to feel isolated and disconnected from the college community. Their pay does not take into consideration the hours they spend helping their students and prepping for their classes. The faculty union has also argued for adjunct instructors to be paid for at least one office hour per week.

“They are paid for only the hour they spend in class. They are not paid for prep time,” said Barnes.

Without an office hour, Essinger does not feel he is as effective as can be.

“One of the ways I can be effective is to sit down with a student and talk about what problems they may have,” said Essinger. “If I just drop in class and answer what I can in front of the group, I’m a performing monkey. There is a lounge where I can meet with students, but it’s not like having an office hour. It’s not like students can knock on my door and say ‘professor can I talk to you?’”

Barnes says the union will continue the effort to get some parity in pay for adjunct instructors.

“As a federation, we believe in equal pay for equal work. We value our part-time instructors equal to our full-timers because they add even more so to the teaching profession,” Barnes said. “Any praise you can give a part-timer is much appreciated. They do a lot for our students.”