Family History Not Always Related to Breast Cancer

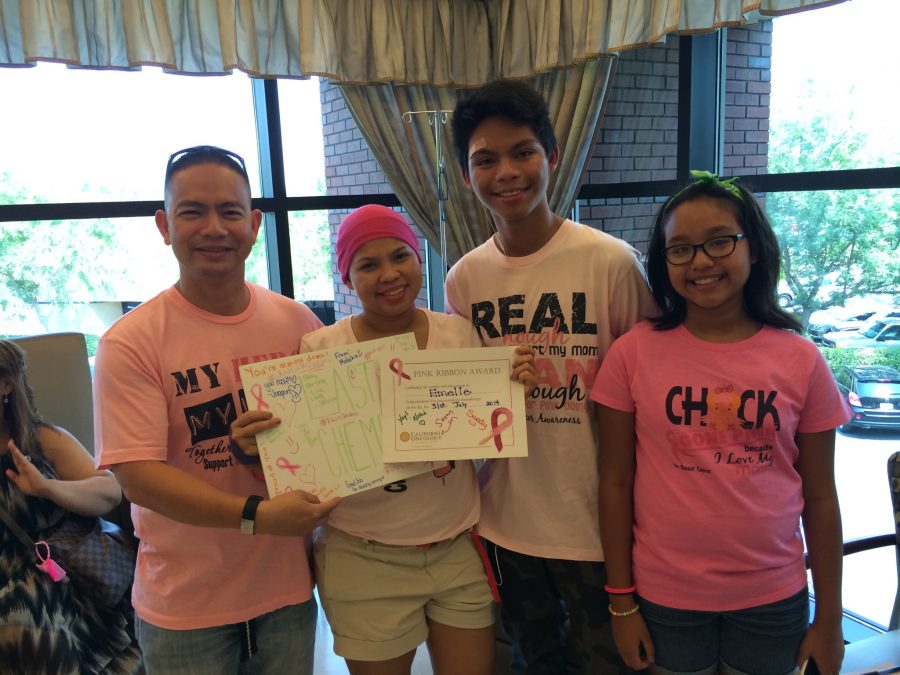

Photo by: Emilie Buendia

From left: Robin Buendia, Emilie Buendia, Lyle Buendia and Malaika Buendia. Emilie was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, despite having no history of breast cancer in her family. She ended chemotherapy in September 2014 and ended radiation therapy in October 2014.

Breast cancer isn’t part of Emilie Buendia’s family history, but at 47, the mother of two is in remission after being diagnosed with the disease two years ago.

“It hit me like a wrecking ball,” Buendia said. “It hit me so hard.”

About 85 percent of breast cancer cases often occur in women who have no history of the disease within their family, according to U.S. breast cancer statistics.

When she was diagnosed at 45, Buendia considered herself a healthy person. In April 2014, as she scrolled on Facebook, she came across a friend’s post claiming she couldn’t afford her chemotherapy after she had been battling breast cancer.

Quickly, this prompted Buendia to self-examine herself for possible symptoms — she located a lump in her left breast.

As a nurse, Buendia was already 70 percent sure the symptoms were of breast cancer. A visit to her primary care doctor for a biopsy confirmed her fears. Her doctor wasn’t sure if the lump was harmful, but further checks would reveal she had invasive ductal carcinoma, the most common form of breast cancer in which the cancer spreads to other tissue.

Immediately, Buendia began feeling differently, contrary to her feelings before she was diagnosed.

“I knew for a fact I was not having these symptoms before,” Buendia said.

A team of people joined to aid Buendia, from an oncologist, social workers and doctors. As a nurse who works at Saint Agnes Medical Center, she took charge of her disease by using any measure to stay healthy.

Buendia was eventually diagnosed with three tumors in her left breast, leaving her scared it may have spread to her right breast. That was not the case, however, and she was last listed in stage two cancer.

She is currently being treated with a daily dose of Tamoxifen, which she must take for five years. She is currently only a year in. After that, it is not certain whether she will be free of cancer, she said, but at the moment, the medication helps reduce cancer cells and gives her hope it may not return. Still, a visit to her oncologist is required every three months.

Regular check ups are encouraged for even men and women who may think they have no risk of developing breast cancer. Fresno City College Health Services Coordinator Lisa Chaney said, “Sometimes you don’t know you have a risk.”

Chaney’s health office, located on the bottom floor of the student services building, teaches students how to identify a lump in their breast. Several students come for questions, but several others have been referred for further testing, Chaney said.

“The earlier you get a diagnosis,” Chaney said, “you can make a more informed decision.”

A lumpectomy is a process of removal of a lump at an early stage, but Chaney advises lifestyle changes to students at FCC. Her advice: exercise, weight control and cutting back on alcohol. About one-third of breast cancer cases are preventable when changes such as these are in place, Chaney said.

“It’s about being healthy, and doing more of that,” Chaney said. “If a woman has a history of breast cancer in [their] family, it’s really important that she follow.”

Less than 15 percent of women who get breast cancer have a family history of it, and the risk nearly doubles when an immediate relative is diagnosed. Younger women who acquire breast cancer often face a more aggressive case of the disease, Chaney said. She said early detection prevents the risk of more chronic conditions in the future.

When Buendia discovered she had breast cancer, she didn’t realize how it would affect her two children — a 17-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter.

For a while, her son would stay in his room, often crying. Her daughter asked questions, one time even asking, “Are you going to die, Momma?”

Buendia said she found strength because of her children’s pain from seeing their ill mother. “It made me realize that I need to fight,” she said.

Now in remission, with a chance she could be cancer-free some day, Buendia says her kids respond to her normally.

“We are living normally right now,” she said, but she still has pain in her bones from the medication she takes.

She says her medication affects the calcium in her bones, something she was surprised to find out after living an active, healthy lifestyle. “It will just come,” she said, explaining that cancer doesn’t have preferences in who it chooses.

Her immediate family is often all she has in her journey to recovery, since Buendia moved to Fresno from the Philippines in 2006. But in her journey and even before she was diagnosed with cancer, Buendia had friends she met through her participation in races for cures organized by the Susan G. Komen Foundation. She said she ran her third race in September.

“Every time I run, I hope there will be news…that a cure is found,” Buendia said. She knows, however that there is no specific day when a cure will be found for the disease that affects at least one in eight women in the U.S.

Wearing costumes and running in all pink is one way Buendia advocates for breast cancer victims. She’s even created friendships with people she has run with, often whole families and whom Buendia treats as close relatives.

“It’s been like our get-together,” she explained. Before she was diagnosed, her nursing background allowed her to remain somewhat knowledgeable about the disease. She now finds herself connecting directly with patients who find themselves in the same situation, she says, acknowledging some may be in more severe stages of cancer.

“I’m lucky I am in a stage two,” she said.

However, all the fears are still there for Buendia, who says she reminds herself that “life is short.”

“In the back of my mind, I always have that thinking that one day I will end up dead,” she said.

Until she met a friend, Sherol Naguiat, who is in stage four of cancer and who has been an idol — an inspiration — for her in the recovery process. Naguiat, according to Buendia, is a happy person.

“Talking to her made me realize that it’s not the end of the world,” Buendia said. The two women consider each other “chemo buddies.”

As she continues to recover, Buendia notes that the most important part of the recovery process is to take control of her journey. It is something she learned from her friend.

Remaining hopeful and often praying, Buendia treats herself to relaxation which she has learned to embrace through her friends.

“Always be in control,” she said. “It’s not the end of the world.”

Cresencio Rodriguez-Delgado has led the Rampage for four semesters as the Editor in Chief. Cresencio joined the Rampage on January 12, 2014 and has reported...