It’s a new school year at Green Valley High School in Henderson Nevada. A young and athletic Samuel Montano walks into his psychology class. The only thing on his mind-the next soccer season starting in a few months. On the board reads “Ms. Pinaro,” his psychology teacher. She is an educator who influenced and fascinated Montano through her lectures. To him she had cracked the door to a new world for Montano, a world he would soon explore and conquer as he pursued his education.

From local to state championships the rest of his high school life was soccer, soccer, and some more soccer. Montano spoke fondly of those times, wearing a cheeky smirk on his face as he recalled cherished memories. Motano noted his brother to be a big part of his upbringing as well, acting as partners in crime. His train of thought carried him to a time where his inner child played.

It wasn’t until right before college that a pivot in his life was made. While picking his major, an unsure but curious Montano recalled how much he enjoyed psychology and jumped at that. “I was really lucky to connect to psychology,” he says. “I think it was always there.”

From childhood Montano was connected to his own emotions as well as others, wanting to provide an outlet for people to share and talk about their feelings throughout his adolescence. He attributes his early emotional intelligence to his mother.

“My mom was very supportive, very nurturing, always willing to engage in difficult dialogue as I was navigating life,” he says.

Montano strongly advocates the importance of parents speaking to their children about feelings and difficult subjects. “It really goes a long way in a child developing their capacity to get comfortable with emotions whether they’re good, bad, ugly or everything in between,” he says.

Montano’s first two years of college were mostly uneventful and his studies didn’t pick up until the end of his sophomore year. At that time he was getting involved in research labs, conducting research with graduate students and assisting in projects. The first milestone in his career was getting one of these research projects accepted into a conference, expressing how excited and happy he was to see his name on the poster for it.

He reached a level of involvement with his work that drove him to solidify his resolve. “I was like ‘yeah I really really wanna pursue this, not just get a bachelors I really really want this,’” he says.

He describes his grad school experience was a hefty one. “It’s a gnarly journey,” Montano says. Between participating in practicum exercises as a psychologist in training to writing his dissertation, things got overwhelming at times. Montano often missed out on events with family and friends from birthdays to holidays. “You see your friends getting married, and you’re just in the books,” he says.

Despite all that, getting accepted into grad school at all is considered to be his first big achievement, and had never sought to abandon his work or field. In his eyes, every obstacle in his way was simply something new he was bound to push through, keeping a steadfast mindset through it all.

He spoke of his personal achievements proudly. Among his milestones was a “beast,” his hardest yet, his dissertation. This lengthy document compiled of years of research within his field in which he must present to a committee in the hope that it gets approved, earning his doctorate. He detailed its process, from researching to defending his research. His battle for completion would last for three years.

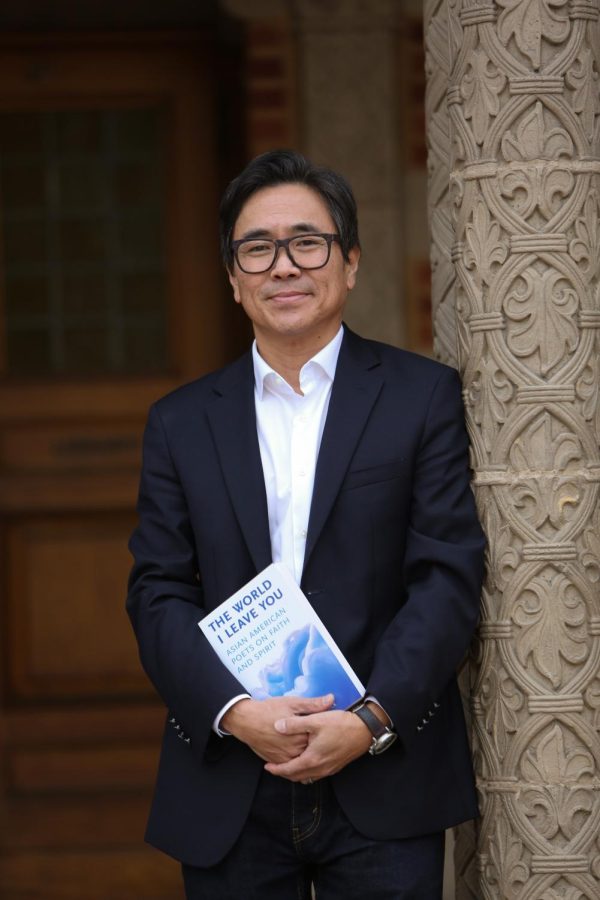

As he spoke, his tone was quiet but passionate, a look of joy and determination was strewn about his face. He has a friendly demeanor, soft spoken, genuine. Every so often while talking, his hands and arms will move softly through the air, as if to add slight punctuation to his relaxed body language.

He stands around 5’11 with a shaven head and glasses, wrapped up in a dapper suit with leather shoes to match. A quick glance around his office can tell you where his interests lie. A wall of a bookshelf sits behind him. Beyond just books it also contains Greek mythology statues, Harry Potter paraphernalia (he’s a Slytherin by the way) and even a porcelain vase in the shape of Thor’s hammer head.

Montano also loves the outdoors, from camping, hiking and fishing to Krav Maga all sitting among his set of hobbies. He preaches that individuals should not only have a healthy mind but a healthy body too.

“If something is physically wrong with you, you see a medical doctor. You break your arm, you get a cast. I think mental health is very much the same thing. You’ve gotta be tending to it,” he says.

Montano’s relationship with Fresno City College and the district started young in his career. Only a year into grad school his first practicum experience and internship took place in the very clinic he now works in and operates.

As Montano’s schooling evolved, so did his role in the office. Eventually he completed his postdoctoral training at Reedley College. “It’s really neat to be so connected here,” he says. “Very deep roots, and a deep love for state center and Fresno City.”

FCC wouldn’t be his first job out of school but rather UC Merced, where he spent the first three years of his professional career.

When the coordinator position was vacant at FCC, he was enthralled. The prospect of being involved with the students at FCC and having a hand in the training program on campus meant a lot to him. “I know how beneficial it is and how much the training here helped me in my formative years. I was like ‘I have to go back’” he says.

“We cut our teeth here at Fresno City,” Montano says with pride. Working at FCC is demanding in Montano’s eyes, but offers great rewards. “There are those things that come along with this job that really bring a lot of happiness.”

Equating his role to a dream job, he expresses his desire to always have been in some sort of director / leadership training position. “I love seeing other clinicians growth,” he says. Seeing the eagerness and their drive to learn is something that motivates Montano to keep doing what he is doing and to give back not only to them but the students.

“I have such a deep love and respect for all of the students here and what they go through,” he says. He believes that a college is the perfect place to break the stigma around mental health by showing students that it’s okay to seek out services and it’s okay to ask for help. “My favorite thing about this campus has to be the students,” he says with a smile. “There’s a lot of motivation, there’s a lot of resilience, there’s a lot of life energy.”

Montano is motivated by his family, psychologists, and students, but his psyche serves as the base of it all. The subconscious inner dialogue that we all have. It tells us if we are happy or sad, whether to cry or stay strong, whether to like someone or hate them.

“You never know if my psyche is going to one day say ‘hey Sam, it’s time to go down a different route.’ Being attuned to what’s going on internally…you never know where life may take you,” he says. He notes that if people lived in harmony with their psyche, people would start to feel happier and do better.

But even still today, Montano continues to do work outside of FCC. In 2020 he published a collaborative research paper alongside two other psychologists that urged counseling assessment centers to better assess psychological symptoms before coming to a diagnosis. Montano’s goal was to study and analyze the main tool / method (Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms) used to draw such conclusions and test its reliability across various populations. “You don’t wanna ever take the one size fits all approach in psychology,” he says.

Montano concluded that the method proved reliable for the most part, although aspects about it were less accurate than others across multiple cultures and backgrounds. “The driving force behind [researching] it is to make sure that the instruments we’re using in psychology are as accurate as possible,” he says. “Unfortunately many instruments are normed on a very select population, a lot of the times it’s not very diversified.”

But the work doesn’t stop there.

In 2021 Montano would contribute regularly to Res Gestae magazine, a monthly publication aimed at helping ex-felons and inmates re-enter society. As part of a larger program a major aspect about it was to help ensure former inmates mental health was tended to.

“Publishing is something I’m really passionate about,” he says.

With extensive knowledge on psychology, Montano is more than versed in his field. Just because he received his Ph.D. doesn’t mean he stoped his studies. “I’ve always thought that a good psychologist is one that is constantly striving for knowledge. You can’t ever get stagnant in this field,” he says. “You’ve always gotta be reading, you’ve always gotta be researching, you’ve always gotta be continuing education.” From the books to seminars and trainings he keeps his mind sharp. He recently finished a year-long certification with the C.G. Jung Institute of Los Angeles. Also, he is completing additional trainings on dream work and dream work analysis. “I’m constantly seeking out new opportunities to learn,” he says. As of today he continues his work on a study around the reliability and generalization of the gender role conflict scale, a scale used to measure men’s personal and relational distress.

A Ph.D. is a monumental achievement for the people who can complete it. Some work a decade or possibly more to receive their certification and finish their academic journey. While this is true for Montano as well, he professes that his true personal achievement aside from academics is his family and marriage.

Getting hitched in October of 2023, he gushes about his wife Valerie Del Rincon (technically Montano now) and their relationship of five years. “I’ve got a wonderfully supportive wife,” he says. Montano’s tone shifts, becoming softer, speaking slower. In between words I could see the gears turning, assuming only gleeful thoughts rushed through his head. “She’s a very supportive individual. Someone I’ve always been able to lean on for support and brings a lot of happiness to my life,” he says.

Del Rincon is an administrative assistant for the emergency department at a local hospital, experiencing the other side of the medical coin. “I Love the ER, it’s its own culture,” she says. “It’s fast, everchanging…it’s just fun. You never know what you’re going to get.”

They met during their time together at UC Merced starting their relationship as a professional one. “I admired him and just the way he practiced and the way he cared for patients. You could just see it through his work,” Del Rincon says.

Once their time at Merced was up, their bond flourished with DelRincon recalling one of their first outings together.

The duo would embark on a hike through Pinnacles National Park. In an attempt to impress each other and seem more athletic or “good with nature,” a friendly competition would ensue. In an effort to show-up the other, the duo became lost straying to the opposite side of the park from where they entered. “He’s the one navigating the whole time so ‘he knows’ how to read a map,” Del Rincon says. After five hours of hiking in 110 degree heat with depleted snacks and water, it seemed their circumstances were sub-optimal. Eventually, Montano would navigate them to sanctuary ending the day with no supplies and two worn out hikers. “He’s just so light hearted and fun, and he knows how to make a crisis really smooth,” she says. In her eyes, situations that may be problematic become fun when Montano is around.

Del Rincon’s admiration for him is deep, presenting him as a passionate person who cares for everyone around him, not just his patients. “Just wow. His passion for the field and helping people is just rare, it’s a rare thing to experience,” she says. Del Rincon paints Montano as a pure hearted man and a hard worker in everything he does. “As a partner, in his professional realm. I just see all of the dedication and the continuing of furthering his knowledge,” she says. “Some people get their doctorate and they just stop. But he continues to educate himself and expand his knowledge for himself, for his patients, for his colleagues.” Del Rincon mentions this as being one of his greatest aspects but also his most problematic, working so hard as much as he does acts like a double edged sword. “He’s constantly like ‘what could I do to be better’ or ‘could I have done that a different way,’” she says. “If only people could see what he’s really doing. If he could help everyone and see everyone a day, he would.” Even on his off days he constantly needs to be productive, putting himself to work at all times. “I love the field that he’s in,” Del Rincon says. She is a mental health advocate herself maintaining the belief that everyone goes through trials and tribulations, admitting struggles of her own. “If it weren’t for psychologists or psychiatrists or the professionals in that field I myself probably wouldn’t be in a good spot,” she says. “I have a huge huge respect for what he does. It can be heavy, it can be really heavy. But it can also be very rewarding, helping people get to a place where they’re living their authentic selves and lives.” According to her, Montano is a selfless, hardworking man with a big heart and bigger passion for what he does. Raving about her husband, Del Rincon’s tone is one of joy paired with a grin from ear to ear, communicating her own passion perfectly.

Although acknowledging the peace and comfort his wife brings to his life Montano admits being away from the rest of his family is one of his most difficult challenges as they reside back in Nevada. “Coming out to Fresno where I didn’t know anybody. I mean literally nobody. Being so family oriented, that was very very difficult,” he says. It’s hard for Montano to go home, calling back to the struggles of missing birthdays and holidays. Being separated from family has been a struggle since grad school.

Working alongside Montano in the office is Dr. Michael Reda, a staff psychologist at FCC. His roots go deep as well having served his clinical internship at FCC as well as completing his postdoctoral training on campus too. Due to Redas history, his relationship with Montano goes back a couple years, stating Montano knew him right as he was crossing the finish line for grad school and during his first career choices.

Their introduction would come about at Redas first interview as a trainee. Applying for his internship, Reda describes the process as a “complicated national match service,” that interns must go through. “Fresno [City] psych services gets applicants every year from all around the country, maybe even some internationally. I was no exception,” he says. “I was lucky enough to get an interview offer from Dr. Montano himself.” Adding that the interview process involved a few head figures from the office, Reda explained one of these head figures to be a postdoc that shared his ideas and theories of psychotherapy. He says it was fairly rare to find within modern day practices. Enlisting in their help, Reda says Montano did this strategically. “It was a little bit of a test, a test that was meant to simultaneously bring my anxiety down if I did know it,” he says. His first interactions with Montano were much less stress inducing than he may have thought. “It was very much more like a conversation, it didn’t feel like this intense ‘oh wow here’s this high and mighty director that I have to like really show my stuff to,’” he says.

Interview processes are tough and important, come spring time new trainees are brought on to the team and the workplace dynamics must be strong. “He’s very much in the mind…of developing a team understanding. Who are all the trainees that are coming in? How are they going to mesh well with each other,” Reda says. During my interview with Reda he points out an outreach for psych services going on outside the bookstore on the floor below us. “One of our prac students, who isnt even scheduled to come in on Monday’s came in today specifically to help out there and interact with the interns,” he says. “That’s something that I think a lot of administrators only strive for within their team.” When hiring people most competent for a job, it’s a sometimes rare added bonus that they mesh well with everyone else they work with. “That’s where his hats of clinical psychologist and director intersect,” he says. To Reda, Montano is able to develop enough of an understanding of these people to best meet their individual needs and see how they might work together two months into the job, six months into the job and so on.

All psychologists in their field must have a level of understanding and competency when reading other people, Reda believes Montano to be a “specialty” case. Due to his extensive history with the college and coming back to run the office he started in, it adds a lot to how well he runs things, along with just his personality. “He’s a guy who genuinely values those kind of work relationships. Certainly I’ve experienced that in my work relationships with him too,” Reda says. “It really does show he goes the extra mile to fit those puzzle pieces together.”

At times though, a heavy focus on team dynamics can cause difficulty when there is conflict, specifically, it may be hard to acknowledge and address issues that can come up within the workplace. Reda explains that when Montano must involve himself within conflict with no objective right or wrong answer, the mentality is “Man I care about both of them in the situation, one of them is going to walk away from this encounter not happy.” Reda says that although conflicts have been solved accordingly and amicably he wishes that certain situations could have been acted on faster by Montano. Admitting himself that some of that wish comes from his culture. Hailing from New York, Reda believes if someone has a problem they must make it known rather than dance around the issue. “Sometimes we dance around conflict a little too long and let things marinate before we find a resolution,” he says. “It’s just something that could be a faster process.”

Reda recounts Montano’s best quality is his versatility. During trainee revision days, trainees will get three hours a week to confide in Montano and voice their concerns, stressors and thoughts about their work. “He comes into that with a stance of being ready to meet you wherever you need that,” he says. Whether someone wants to strategize how to not lose track of their progress after a stressful week, or if they’re in distress after a heavy week of clients experiencing suicidal thoughts, Montano is there to help. Even if a trainee just wanted to nerd out about psychology for their time, he’s there for that too. “He can switch between those things on a dime based on the needs of the trainee,” Reda says. “You need flexibility, you need versatility, you need to be able to go with the flow but in a concrete way. That’s probably the thing that I most appreciated about him both as a trainee and as a person.” In Redas work experience, he’s collaborated with people who can think in the present or the future, not quite both, but Montano is someone who can go between them simultaneously. “He doesn’t have to sacrifice a future vision to meet the needs of the clinic today,” he says. Reda stated how his type of personality is able to bring down the anxiety of everyone in the clinic and makes it a fun place to be in.

Adding to that, Reda feels “approachable” goes hand in hand with these statements. “Whenever I’ve needed my supervisor to provide some guidance or to step in on a really high intensity situation, he has no problem stepping out of a meeting to help the needs of a student,” he says. Montano never goes into a meeting and says “you’re on your own.” Instead it seems he holds everything and everyone to such a high level of importance that no matter the situation he will drop everything and support in any way he can.

Psych services at FCC is a crisis clinic, and at times those high intensity situations do occur. “We unveil ourselves to crises when they happen, we wanna be there for students when their mental health is really really in dire straits,” Reda says. Recalling an experience of his, he speaks on an incident that occurred last year spanning about five hours. Himself and all the other staff had been taking turns trying to do the best they could for the students who needed help with Reda, comparing it to “a revolving door of practitioners.” At the same time psych services was communicating with other departments around the campus who were involved with Montano needing to keep track of each individual in the office, staff or student, all at once. After it was all said and done and the situation was resolved it still seemed bittersweet. “You have this pretty often in mental health. Even when you know you did the right thing it still weighs heavy,” Reda says. Often over the course of knowing a patient and getting deeper into their case, patterns can occur. Missed opportunities and poor choices can lead to situations that cause someone to look back and think “it really didn’t have to come to this.” In the aftermath of this, Montano had sat and debriefed his staff on what took place one on one, not caring about staying past his clock out time and being more than ready to comfort his colleagues. “He has no problem staying late in order to make sure that like, we’re okay. To come back tomorrow, do it all again at 8 a.m.,” Reda says.

He confesses that at that time he had a form of impostor syndrome clouding his mind, trying to form his own professional identity he found himself confused, not quite accepting his new title. Once he was debriefed, he expressed happiness and relief, stating Montanos feedback made him feel good about himself and a bit more secure. In the weeks that followed, Reda says Montano was with him every step of the way, relating to and comforting him. “He was just able to meet me in that moment and even give words to something that I really wasn’t entirely sure how to give words to,” he says. “I stumbled into it and then he was just able to kind of like summarize it like ‘yeah sounds like you’re feeling this.’” Once resolved, Reda tells that it was a learning and growing experience for all the staff involved. Come the next semester he was ready to “hit the ground running,” attributing his motivation to Montanos words of encouragement. “I just had that affirmation from a director who’s seen it all,” he says.

While Reda wrote his dissertation it was one of his hardest challenges. He tells of when he had to defend it to his committee for his final revision. With the only time slot being on a work day, he had rushed home after revisions in the office to attend Zoom meeting and finished with the day to spare. “It was very anticlimactic when they told me that I passed. I had been writing this one paper for five years and now it’s just like ‘oh you’re done you passed,’” he says. Arriving at the office the next day, he would debrief with Montano, describing a sort of bewilderment. “I had a supervision with him that was just very real,” Reda says. “He just dropped everything he had and met me in that moment.” He feels that a lot of supervisors would have offered a few different solutions. From focusing on what you can control now and being productive to implementing self care practices so that productivity is not hindered, each coming from someone who is a boss first, they want their employee happy but also productive. Although those solutions aren’t wrong, Montano however, didn’t see Reda as an employee there, but as a human. Interacting with him not just as his boss but one person to another. “‘If I just attend to him as a human being all of the other stuff will fall into place he’ll pick himself back up,’ and that’s exactly what happened,” Reda says. “He just really went above and beyond for me at that really sensitive part of my professional journey and I’m a better psychologist today because of it.”

According to Reda, often there are a lot of sites and clinical directors that see trainees as a business investment first, free labor paid in experience not money. “I haven’t felt that at any stage of my training here,” he says. Never experiencing that he was just a cog in the machine. Making it a point to say that he doesn’t just fill an empty position based on if they have a degree and a pulse. Reda feels Montano to be an exception to this trope. “He’s heard his fair share of horror stories of how people that enter the helping profession truly valuing the work that they do with patients, and then just having that weaponized by hospital administrators and staff,” he says. He believes that this motivates Montano to have a deeper love for the trainees that just want to help people.

Every year psych services holds a “Hello Goodbye” party for the staff to not only send off the interns who finished their time at FCC but to welcome the new ones in. After having a bonding year with his colleagues Reda tells me at his going away party was a fun way to let loose and have a good time. But what (or rather who) really made the night shine was Montano. “This guy shows up on the last day of our internship, ready to party,” Reda says. Decked out in hot pink crocs, short shorts, a t-shirt and shades was the doctor himself, ready to sign the documents that finalized the internships of the staff. “Anybody coming in thinking ‘oh this is like a work party’ no this is just legit these people are here to party,” he says. “You would not know that this is our guy, that this was everybody’s boss.” Showing a different side of him that was just Sam, not Dr. Montano, adding to his aforementioned versatility.

Reda has been at FCC for two and a half years, being quite the experience he commends Montano for the work he has done. “I can’t imagine doing that with anybody else as director. He’s just made it a really fun place to work that is super oriented on growth,” he says. Reda states his own contract with FCC is up at the end of this semester with Montano helping him prepare for his next steps as he moves into private practice. “Even as I have one foot out the door with Fresno City Psych Services, he’s still just helping me as a friend, just generally wanting me to succeed to matter where I go in this field,” he says.

“This is someone you can trust,” Reda says. With 20,000 students and only a handful of trainees and two psychologists at any given time, those numbers are staggering on paper. “This is someone you can trust to make the most of what we have with the resources that were given by the college.” To Reda, Montano is not someone who just oversees his therapists and strives for good care for his students, he goes to the Academic Senate and advocates for mental health needs on a systemic level. Montano goes to meetings with upper administration to stay steps ahead of any incoming problems before they can turn into larger issues. He is someone who shows up to mental health outreaches as well, not just an overseer invested in his own agenda. “This is somebody that is both advocating at the upper levels as well as in the trenches with the trainees,” Reda says. “So this is somebody who is forward thinking and grounded simultaneously. That is somebody with a vision you can trust, when you’re in a very sensitive spot. When you don’t really know where to go, how to keep going with college or life. When you’re just looking for hope, and wanting to feel safe.”

The job that is done by Montano and all other psychologists is a fascinating one. Often not seeing the result of their work, patients only attend sessions for limited amounts of time. “They may be with us for a handful of years and then they carry on,” he says. “You’re walking into a movie halfway through and you’re only staying about 10 minutes of that movie.”

Similar to how a chef prepares a meal for a hungry patron, the chef does not witness the meat be butchered nor the vegetables picked. Nevertheless they take the ingredients presented and fry, chop, season and prepare. The chef exudes passion and resolve into the plate, trying his hardest to keep the dish together and perfect it. The chef, however, does not get to see the result. The patron has undoubtedly received their masterpiece but the verdict is unknown, leaving the chef nothing but a thought to ponder.

Montano does witness growth, whether it be a patient breaking a painful behavior or a change in attitude, but reiterates how you only see that one snippet of their lives.

But sometimes he does receive that sense of completion. Luckily, there is the satisfaction of knowing he has truly made a positive impact in someone’s life. “Oh it’s profound, it’s profound. It’s why I do the work. I am always humble to remember though, that it’s the patient that’s done the work,” he says. “They’ve got to see they’ve got the tools within them, to heal,” he says.

It is undeniable in this period of history that we as a species are seeing unprecedented phenomena related to mental health. Especially in Gen-Z, my generation. Gun violence in schools, expensive housing, the effects of social media, the uncertain future of our own country in America, the list just goes on. “There’s a lot going on in the world…a lot, and Gen-Z folks have been through quite a bit,” he says.

According to a study released by the American Psychology Association in October 2018; 56% of Gen-Z in school feel stressed at times considering the possibility of a shooting at their school. A more shocking figure reveals, 91% of Gen-Z between the ages of 18 to 21 say they have experienced at least one emotional or physical symptom of stress in the last month.

When examining these findings Montano suggested a main contributor to be social media and media as a whole. He believes there are many positive effects that have been made as well as negative ones. “A lot of the time news is there to educate, which is great. But if you’re constantly getting bombarded with really negative imagery or stories it can be very tough to see,” he says. A common strategy to combat this with patients is to set limits on how much media and news they consume. Instead of watching the news for three hours, try 20 minutes.

A side effect of technology today is the recurrent “iPad kid,” a term used to describe children who were raised on and introduced to technology at a more than early age. Montano’s philosophy regarding these individuals is largely the same. Believing that technology has the capacity to help children in certain capacities.“Kids gotta remember to get out and play,” he says. “Play is so important. Getting out there, getting dirty. Playing in the mud. Playing tag. Playing sports.”

Montano understands that there is a place for online connection, yet he also recognizes how much more impactful an in person experience can be. Just going for a walk and talking to someone or grabbing a coffee with them can be beneficial. “It’s gotta be a balance right? I don’t want to have all my friends online and have none in my general vicinity where again, I can get a coffee with them,” he says.

Accessibility to psych services is another contributor to this trend of psychological distress. Montano tells me students will take one unit classes at FCC just so they can have services. “But in the community, it is tough. There are so many barriers. If you go see a licensed psychologist here in Fresno, the average rate is $150,” he says. Even with insurance, some individuals can only get so much out of services before they have to pay out of pocket. “They may say ‘we’re only going to give you five sessions.’ When in reality they probably need like 15 or 20,” Montano says. He urges that this is one aspect about our society that needs to change and be addressed.

Furthermore, hospitalization methods and treatments must also change. Montano provides a hypothetical: assume an individual is put on a 72 hour hold off a 5150 call (the number of the section of the Welfare and Institutions Code, which allows an adult who is experiencing a mental health crisis to be involuntarily detained for psychiatric hospitalization when evaluated to be a danger to others, or to himself or herself, or gravely disabled). The patient is then released immediately after with some medication, without a second thought. If an appropriate follow up is not provided they may likely be doomed to repeat the process. “This is not just a current issue, this is a pervasive issue,” he says, with real life examples of this happening all the time. “If there was something that can be done in the future to provide more treatment that is tailored to the problem, not just the band-aid fix,” he says. But he admits that these would need to be massive systemic changes.

Speaking on treatment options, therapy is not the only way to go. It’s recommended that taking medication along with psychotherapy is the more effective route for most situations. But in my experience and many others who have grown up with their own conditions, there is a stigma around taking medication with many adolescents and young adults being abrasive to the concept. “I think medication has its place,” Montano says. “For some situations medication can be very helpful. I think in other situations working through in therapy may be the better alternative than putting someone on medication and saying ‘hey just do this,’” he says. As stated by Montano medication must be thoroughly understood. Doctors must go into great detail on what the medication is, how it will be used, its side effects, etc. When dealing with kids from the elementary to the high school level the same goes. “The parents really need to understand, the parents need to really ask the questions and be attuned to what their children potentially may be taking,” he says. It’s most crucial to ask if medication is the right thing to do in a collective discussion, while also involving the child at some level.

According to a study published by Best Colleges in February 2023; a survey of over 54,000 undergraduate students found that 77% have experienced moderate to serious psychological distress, 79% experiencing high levels of stress in the last 30 days and 12% purposely injuring themselves in the last year.

Presenting these facts to Montano, he was quick to believe its accuracy. He recalled a study that was conducted in 2020 throughout the college district where around 600 students were surveyed. “The numbers of depression, anxiety were quite high,” he says. Even more staggering was the rate of suicidal thoughts, especially among LGBTQ+ students. “They are exposed to more discrimination. They have traditionally been a group that has had higher levels of mental health issues, but that is likely because of the impact of society,” he says.

On a different end of the spectrum, a survey published by the Survey Center for American Life relayed that 55% of men in 1990 reported having at least six close friends, in 2021 that figure shrank to 27%. Additionally, the number of men who reported having no friends increased from 3% to 15%. This among numerous other studies suggests men are getting lonelier, with the term “men’s loneliness epidemic” being tossed around.

This is another set of statistics that is unsurprising to the doctor. “It’s very alarming,” Montano says. “We are social creatures, we need friends, we need people to lean on.” Portraying men as notoriously bad at reaching out when they need help, Montano contributes this to the societal stigma around men’s mental health. It’s something I have experienced and relate to. “Men are a lot of times brought up to be strong, self-reliant, competitive, non-emotional,” he says. Citing that these social pressures may lead men to isolate themselves. However, Montano has hope for the future as more people include this issue within their discussions.

“Each group of folks is going to need a different way of connecting with them,” he tells me. “What may help a woman may not help a man, what may help a man may not help someone who identifies with the LGBTQ+ umbrella.” This, according to Montano, is why you must have culturally diverse and trained clinicians. Urging that all dynamics throughout many walks of life must be covered.

A true test of character is often proven when someone wins the lottery. Will they donate it? Buy crazy expensive things? Will they disappear to Argentina? All these questions are valid. Montano however shows a charitable aspect of himself. Having asked the question, his first response was to give to SCCCD. “They’ve done so much for me,” he says. “I would undoubtedly give to State Center, and the psyche and health departments here.” This reinforces his commitment to where he works and what he does. Montano continues his barrage of charity, he fantasizes giving to charities that support the environment and conservation, citing the importance of “tending to our natural world.” Outside of that he would mostly save his money. Aside from traveling a bit, buying a nice house on the Central Coast and settling down, he expressed not being attracted to extravagant things, harboring a humble mindset. “It doesn’t need to be some big thing. You know I’m not that guy, I’m really not. I mean I drive a Corolla,” he says with a grin. Although retirement is quite far from Montano, his hope is he can achieve these things eventually anyways.

Psychology is defined on Google as, “the scientific study of the human mind and its functions, especially those affecting behavior in a given context.” Montano, however, believes it goes much deeper. He attempts to communicate the feeling of psychology, struggling to find one single descriptor. “The feelings are constantly evolving. I think that’s the beauty of the work, it’s never one thing,” hey says. “There are moments within sessions where you feel good, you feel happy.” A patient making a breakthrough, or gaining a new perspective can be “wonderful” and “heartwarming.” “There are other times you see your patients really struggling,” he says. The office he works in is a place where many traumatic things are heard. Admitting there are times you may feel sad, he describes feelings of “frustration” and “disgust” while listening to things his patients have gone through. “The feelings are constantly changing. But that, in all honesty, makes it somewhat beautiful. You’re on this path, you’re on this journey with your patient, and there’s something really powerful about that,” he says.

“One thing I would like the Fresno student body to know is that I’m always here for you. If there’s anything that I can do to help. If there’s anything I can do to support, let me know. I will do my very best. I want you to know I’m very student focused and wanting to provide the gold standard of treatment that we are able to do in the confines of our clinic, to help students,” Montano says.

This article was edited after publication to correct “Union Institute and University of Los Angeles” to “C.G. Jung Institute of Los Angeles” on Feb. 5, 2024.