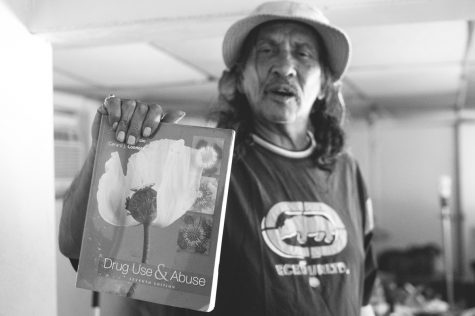

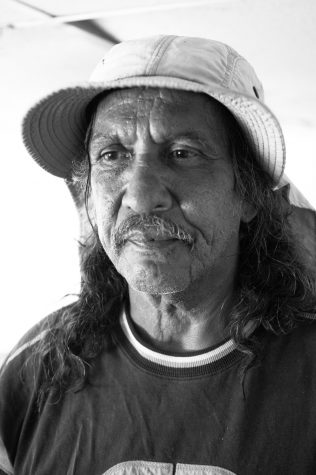

Photo by: Ram Reyes

An Odyssey of Hopelessness

South of downtown Fresno is a place most people usually avoid. Desolate and littered with trash, most of its inhabitants are either homeless or are the few small-business owners who have stuck around through the years.

The place is Chinatown, and it is home to one man and his dog. In a small, run-down former business front, Larry Rodriguez, 63, and his canine companion Zapata, live in a cramped hallway on the second floor.

The space is littered with miscellaneous items; old toys, broken flashlights and glass bottles are strewn about the room.

The fridge, located on the far end of the room, is filled with rotten food. Power had been shut off in the weeks prior.

A broken glass bottle and a candlestick sit on a TV tray in the middle of the room and is his only source of light, Rodriguez says.

The Fresno City College student says his life wasn’t always like this.

Originally from New Mexico, Rodriguez lived his young life on the Mescalero Apache Indian reservation until the 60s, when he arrived to South Central Los Angeles as a fifth grader.

“I grew up in a rugged neighborhood in South Central LA which is considered one of the worst neighborhoods in the area,” he said.

Rodriguez said that around the time he entered high school, he became a violent person and found himself in the California Youth Authority, now known as the the California Division of Juvenile Justice, which educates and trains serious youth offenders.

Things seemed to be looking up for Rodriguez, but after a couple of years at Los Angeles City College, he again found himself on the wrong side of the law.

“This dude was jumping some of my friends and there just so happened to be a crowbar there, so I went in swinging. I wound up doing some damage and was sentenced to prison for about three years for assault with a deadly weapon.”

In 1975, after doing his time, Rodriguez says he worked as a counselor for violent teens in Los Angeles.

After a year of working, Rodriguez says he decided to move to Albuquerque, New Mexico to pursue a job as a counselor for inmates in a half-way program.

“During that time, I used to work with judges, police, lawyers, prosecutors and psych staff. I was used to all these suits and ties and nice shoes. Look what I got now,” he said, surveying the room.

Rodriguez didn’t last long in the counselor position before landing in jail once again, due to a fight.

He lost his job because of his jail sentence, and instead of staying in New Mexico, he made his way to Fresno to be closer to his mother who had become ill.

He struggled to get a job due to his not-so-clean record and started to work as a telemarketer.

Rodriguez says he was living pretty comfortably after moving up in the company, but eventually lost his job due to drug use.

“I had money in my pocket, but I winded up getting into drugs, and I lost my job on that,” he said.

Rodriguez then began to struggle to find another job to meet his needs in Fresno.

Yet again, he was sent to jail after another assault and spent three years there and put himself into rehab afterwards.

“I told them that it was for that [drugs and alcohol], but really it was just so I had a place to stay because at that point, I was homeless.”

After getting out of rehab, Rodriguez moved into Chinatown and began attending Fresno City College. He acquired Zapata, a chihuahua-mix, one of the rare positive things that has happened to him.

Rodriguez told a Rampage reporter last year that Zapata was given to him four years ago by a neighbor and friend who had passed away from cancer.

“He had cancer [and] asked me, ‘Larry, do me a favor, can you take care of Zapata for me?’”

Still, his bad luck followed him and his companion to Fresno City College.

On Sept. 8, Rodriguez received a letter from the V.P. of student services which informed him that he and Zapata were suspended from the college campus for failure to follow orders to keep the dog under control and off campus.

“[Zapata] poses a threat and danger to the population at [FCC],” The V.P. stated in the letter. “On numerous occasions, Zapata has growled, barked aggressively, chased students, and has been left unattended on the [FCC] campus.”

The ban meant Rodriguez was suspended from all his classes for the fall semester.

Rodriguez said that his financial aid and grants were also being taken away due to his suspension.

“My life has just been destroyed. For the last two and a half years, that’s my only survival,” he said in September. “I will become homeless and, most likely, become a danger to society.”

“Why have I been denied due process?” Rodriguez would later write in an appeal letter to fight the college’s suspension. He also stated in the appeal that he was illegally harassed and discriminated against as described in Administrative Regulation 5530 and that the college administrators were not listening to his story or considering the impact a suspension will have on his and Zapata’s lives.

“Both of us have been in class together; no one has had a problem with his [Zapata’s] behavior; teachers, as well as students, have had no difficulties,” Rodriguez’ appeal letter stated. “How can one person have the power to give an order to make a life unsound?”

Rodriguez insisted that the V.P.’s letter ignored the fact that Zapata is licensed by the city of Fresno as a service dog and is very essential to his well-being. A representative for the city of Fresno said that service dogs are allowed to go anywhere their handlers go unless they are deemed “out of control.” The person is still welcome, however; only the dog is banned.

According to information on service animals, posted on the website of the Disability Rights Section of the U.S. Department of Justice, the American with Disabilities Act does not overrule legitimate safety requirements such as those cited in the suspension letter to Rodriguez.

According to the ADA website, “If a particular service animal is out of control and the handler does not take effective action to control it, or if it is not housebroken, that animal may be excluded.”

Immediately following the suspension, Rodriguez asked students to write letters to Goldsmith, Parnell and Interim Director of Student Services Sean Henderson asking to reverse their decision, to no avail.

“He [Zapata] doesn’t bother anyone anyway. I [have] him on a leash,” Rodriguez said, insisting that his dog is not a threat to students. “I’m a student. I’m entitled to an education, and they are denying it to me.”

Despite the ban, Rodriguez came to campus a few times with Zapata, hoping to meet with President Carole Goldsmith, Interim Vice President of Student Services Rojelio Vasquez and Paul Parnell, chancellor of State Center Community College District.

SCCCD Police approached Rodriguez during his brief visit on Sept. 13 and warned him he could be arrested for being on campus, but did not arrest him.

“I am fully aware that my Zapata could be arrested,” Rodriguez said while on campus. “I was hoping for that result; this way, I would have an audience.”

Rodriguez told the Rampage he would not be able to pay his rent in the following months and would have to live on the streets. He said he has no resources and no access to a lawyer to guide him in this situation.

And as his life has proven, when it rains for Rodriguez, it pours.

About two weeks after the suspension, Zapata went missing from his home in Chinatown.

While out searching for Zapata, Rodriguez said he was attacked with a tire iron by someone on the street, leaving him with a broken arm and a stitched up forehead. Frustrated and frantic, Rodriguez wondered how deep his bad luck could run.

Miraculously, 37 days after he went missing, Zapata suddenly appeared on Rodriguez’s door step, thinner, but seemingly unharmed.

“I swear I almost broke down in tears,” Rodriguez said. “He [Zapata] was just so happy.”

“I was about to give up and hang up the towel,” he said.

Although the ban dropped him from all his fall classes, the letter stated that Rodriguez would be able to attend classes in the spring on one condition–Zapata stays away.

Rodriguez is looking forward to beginning classes in the spring again, but he is still continuing his fight to get Zapata back on campus as his service dog.

He said he will do whatever it takes, including petitions, protests and stand-ins with Zapata.

Rodriguez said almost losing Zapata forever had made him want to quit his attempts to return to Fresno City College after his suspension on Sept. 8, but is now encouraged.

Maybe, finding Zapata is the turning point Rodriguez needs.

“Zapata makes things a lot better,” he said. “He’s like my kid.”