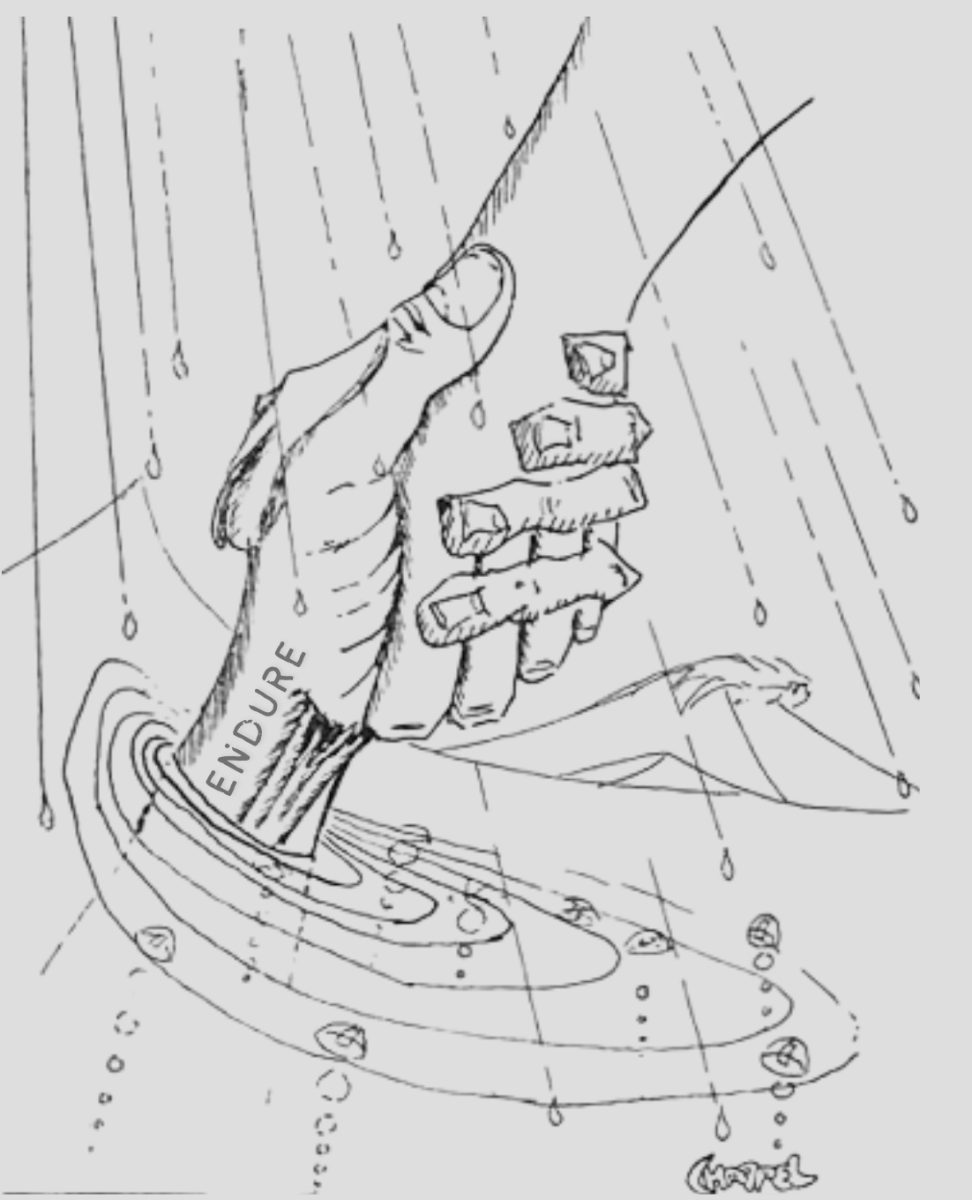

It was one year ago last week that a 16-year-old Pakistani girl was shot in the head by the Taliban for attending school and advocating for universal education. The anniversary was marked not with tragedy and pity, but bravery and resilience.

The Oct. 8 release of Malala Yousafzai’s autobiographical book, “I am Malala,” which chronicles the harrowing incident of a child activist and her personal thoughts and growth, culminates a year of overwhelming admiration for a newfound international icon.

After extensive treatment at Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham in England and a full recovery from three gunshot wounds inflicted by members of the Taliban, Malala Yousafzai, has more than healed physically.

Despite continued death threats from the Taliban to “strike whenever they get the chance,” Malala accepted her nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize and made waves in the media, appearing in television interviews with Diane Sawyer, Christiane Amanpour and Jon Stewart.

The young teenager has become a symbol of courage and resilience for the young and old alike and for men and women of all nations. Her fight is about much more than women’s rights to education. It is about a universal human rights march against oppression of all people.

What is most profound in this inspiring story of a teenage girl is the unabashed truth behind her strong message. Malala opens our eyes to the inequity that plagues the world and about our responsibility to advocate for those in less privileged situations.

Universal education, Malala tells the world, should be a right had by all children regardless of their race, class or nationality. Yet it is still far from a universal reality in 2013 because terroristic threats, patriarchal government regimes, rampant poverty and national instability are ever-present hindrances to achieving such a valiant worldwide goal.

Many consider education to be an inalienable right, yet it is not strictly and equally enforced throughout the world, especially in less-developed countries. According to a 2012 study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 72 million adolescents of primary- and secondary-school age do not have access to education.

This is especially poignant when compared to the opportunities afforded to students in the United States, even at Fresno City College where government provides financial assistance to those in need.

We are given the right to education from kindergarten to high school, as well as opportunities for higher education, all of which we take for granted. Most young people and children worldwide are not as lucky as we are.

In Malala’s home country of Pakistan, the percentage of children who are not in school is the second worst in the world; 5.1 million children (two-thirds of them girls) are not receiving any education, a 2012 UNICEF report states. Just being born female dictates whether or not you have access to this inalienable right.

It is illegal in the United States to deprive a child of education, yet what about those children living an airplane ride away from us, seeking nothing more than a basic education they rightly deserve?

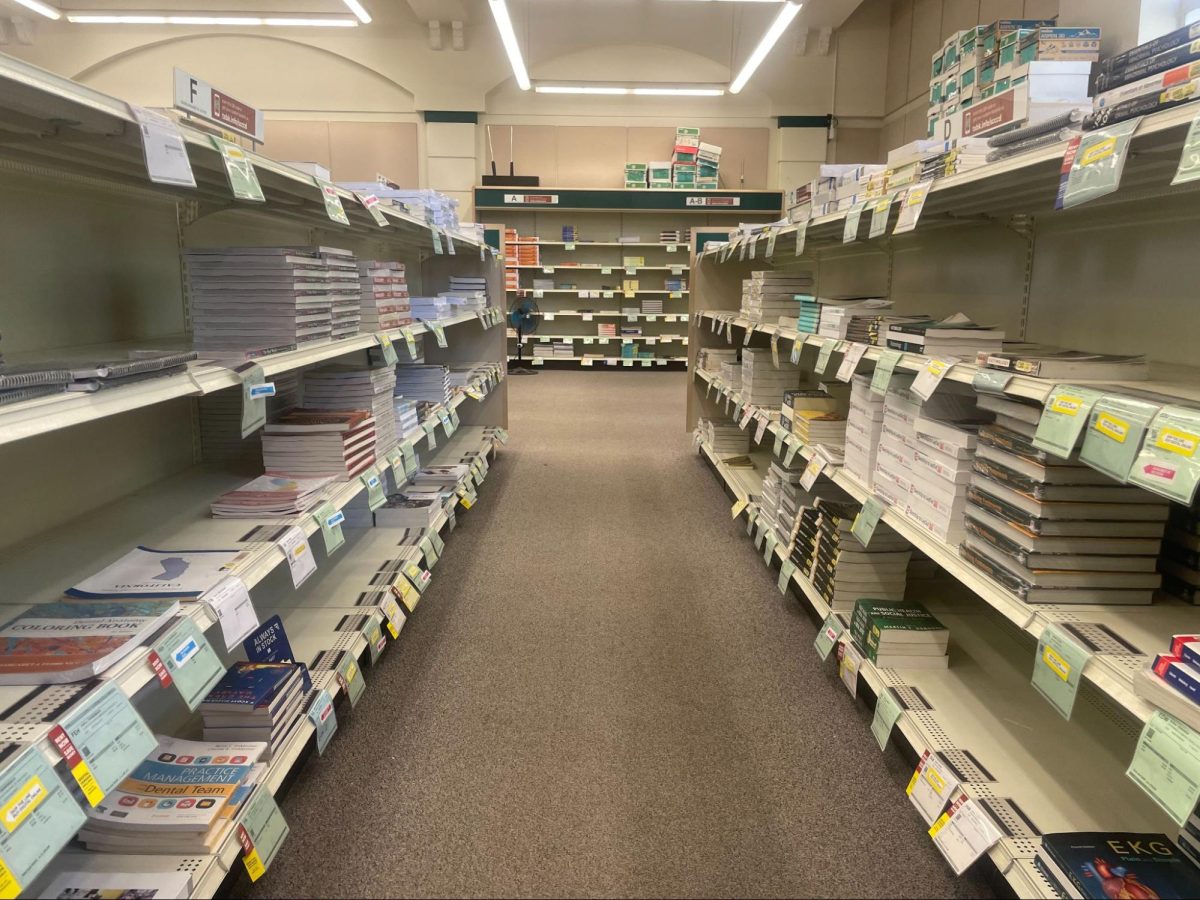

While college students in the United States can receive government financial assistance to help with college, children are deprived of this gift due to poverty, war, cultural practices and oppressive government regimes.

According to the California Student Aid Commission, the U.S. Department of Education gives about $150 billion to college students nationwide each year. The California Community Colleges system, which consists of 112 statewide schools, similarly receives $2.21 billion in financial aid annually to award to California students.

Yet humanitarian-based financial assistance meant to help those in need allocates a disturbingly low proportion of all aid to educating children. A 2013 Global Monitoring Report by UNESCO states that only 1.4 percent of all funding was given to education, with a $221 funding gap to make up for.

The majority of aid, understandably, was allocated for food and health. Yet the message drawn from this is clear: basic aid is not enough, and public demand for educational progress needs a much louder voice in 2013 and beyond.

We, American students, retain privileged status throughout the rest of the world, so it is our obligation to speak out against educational injustice and compel our governments and fellow citizens to take action and remain vigilant.

For what does it say of our own society, of our own FCC community, if we shudder at the thought of children getting shot for their decision to attend school, but blindly ignore the ways we can make a difference?

The easiest way we can stand in support with Malala is to never take for granted the bounty of opportunity set before us, but to take advantage of every chance to excel in school and better ourselves and others. We must all seek out careers and knowledge that will boost benevolence in the world and effect change; we must educate ourselves on international conflicts and write letters to our government leaders, and join clubs, organizations and find friends that push us to be better people and create a better world.

The opportunity to stand in unity with those oppressed is limitless. We must stand to be counted.

Malala is more than a 16-year-old student with a gift for intelligent speech; she is a beacon in the dark for women, girls and oppressed people everywhere. A modern epitome of bravery, determination and female equality, Malala reminds the world that everything is nowhere near satisfactory; that injustice still thrives in our countrymen’s backyards.

It is time for mankind to listen up. Malala speaks about vast and cruel disparities in our societies. And what should our response to this siren song be?

Three words — “I am Malala.”